Conclusion

The analysis of cranial and ontological distinctions of paleoanthropological material in the context of culture-forming processes in the Altai-Sayan highlands and adjacent southern forest-steppe regions of the West Siberian Plain led to several important conclusions on the dynamics of anthropological composition of the ancient inhabitants of this region. In turn, the results of anthropological research presented facts on that draw attention in the interpretation of purely archaeological facts and based on the reconstruction of “scenarios” on the genesis of the historical and cultural phenomena.

The chronological range selected for the study is very wide, from the Neolithic Era (according to modern radiocarbon dating from the 6th – 5th millennium BC) until the turn of eras.

Not all stages of the regional culture-forming dynamics are reflected evenly, and this situation is due not so much to the level of representation of the used paleoanthropological series as to the substrate role of the anthropological component in the historical and cultural development within the follow-up processes of ethnocultural genesis.

Much attention is paid a modest in scope collection of the Neolithic paleoanthropological finds. But the major autochthonous population’s genetic origins of the regional archaeological cultures ascend to the Neolithic stage. Moreover, from the Neolithic foundation of the anthropological build-up, under the influence of the factors of intra-population interactions and inter-population transformation, began to take shape the modern anthropological structure of humanity.

No less important is the Eneolithic period (or Early Metal Period) (2nd mill. BC – 300AD), which initiated fundamentally new technologies for the population’s livelihood and for the inevitable intra-tribal and intra-clan rearrangements of social relations, in turn, ted through the system of demographic adaptations, the biological anthropological traits of populations.

In that historical and cultural period (Eneolithic, 2nd mill. BC – 300AD) is recorded a first transcontinental migration of a compact population group (people of Khvalynsk or Poltavkin Culture), that spun-off from the Pit Grave cultural-historical community and created a new very viable archaeological phenomenon in the Altai-Sayan region, the Afanasev Culture.

In the Eneolithic period are actively forming autochthonous cultures, in the inventory complexes of which are found objects (mostly bronzes) demonstrating links with geographically very distant cultures of the emerging Circumpontic Metallurgical Province (Eneolithic, 3,500-2,500BC).

The Early Metal Period for the indigenous cultures is saturated with unresolved issues of intercultural interactions. Therefore, the search of their reflection in the paleoanthropological materials makes it very important as an archaeological source, although its numbers are very small.

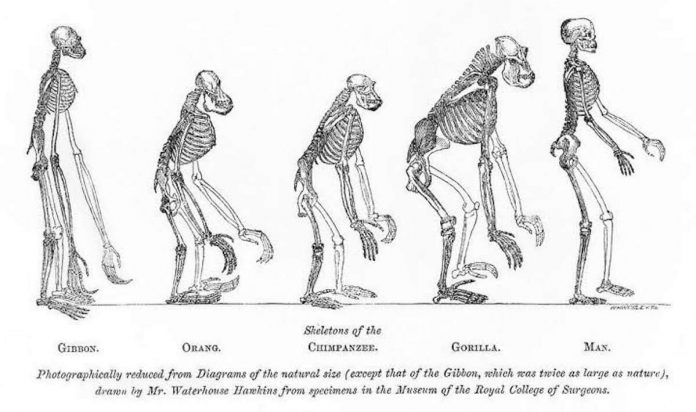

Analysis of Neolithic and Eneolithic paleoanthropological materials in a comparative aspect using available comparative data on synchronous cultures led to a very important conclusion that in the Neolithic Era and at the turn of Neolithic-Chalcolithic in the anthropological composition across Eurasia dominated morphological complexes with incomplete differentiation into consolidated Mongoloid and Caucasoid complexes of the main (geographical) races.

“Incomplete” means neither Mongoloid nor Caucasoid, or both Mongoloid and Caucasoid, and maybe Negroid and Australoid etc. According to the author, “history of racial complexes does not have a single direction – it is not an evolutionary process leading the entire population to the modern races”; thus “incomplete” in respect to the modern “primary races” is not applicable. Rather, the phenotype of the population does not fit into today’s classificatory notions.

V. Bunak identified one of the unconsolidated complexes in varying anthropological variations in the Eurasian north-western forest zone as a separate racial community, which he called “Northern Eurasian Anthropological Formation” (Bunak, 1956, p. 101).

To that anthropological community belong the Neolithic population groups of the Baraba steppe adjacent to the Altai-Sayan upland (Creek, Sopka-2/1) (Sopka is a name for volcanic vent pyramid, also applied to rounded-top hills).

The area of the Northern Eurasian Anthropological Formation enormous area: the main finds were obtained in the north-western (Onega lake, southern basin of the White Sea, Karelia, Baltics) and southeastern (northern Baraba) fringes, and also in the northern forest zone of the East European Plain (Pit–Comb Ware Cultural-Historical Community) (held to be Uralic, calibrated time range 5600 – 2300 BC ).

During Neolithic period in the Altai-Sayan region is allocated another unconsolidated craniological complex, characterized by a meso-brachycranic form of medium height skull, with a complex mix of Mongoloid and Caucasoid proportions of cranial parts, moderate flattening of the medium in height facial portion, high nose bridge with moderate protrusion of the nasal bones over the overall line of orthognathic (without projecting jaw) facial profile.

This complex is visible in the crania of the Neolithic period: female skull from a burial in the Hearth cave in the Altai Mountains, a series from Solontsy-5 burials in the foothills of the Altai forest-steppe, skulls from Bazaikha and Long Lake burials in the Krasnoyarsk-Kan forest-steppe and burial near village Bateni in the Minusinsk Basin.

By analogy with the defined by V.V.Bunak “Northern Eurasian Anthropological Formation” in the transitional zone of northern Eurasia, this author proposed status of Southern Eurasian Anthropological Formation for the ancient morphological layer in the transitional zone of southern Eurasia.

From the standpoint of the ancient protomorphic anthropological communities in Eurasia notable for their distinct intermixed Caucasoid-Mongoloid racial complexes, it became possible to explain similarities between spatially distant groups not only by migrations but also by convergent origin of morphological complexes with partially similar traits, which is especially typical for the Neolithic time (6th – 5th mill. BC).

The idea of Southern Eurasian Anthropological Formation proved to be extremely fruitful, it enabled to explain the morphological idiosyncrasies and reasons for anthropological similarities in the populations of some cultures of the Okunev and Karasuk circle, the so-called “Andronoid” Cultures of Western Siberia, the Early Nomads Culture of the intermountain valleys of the Altai-Sayan upland and foothill-mountain systems of the Dzungaria and Tien Shan.

For at least four millennia the Southern Anthropological Eurasian Formation has been the main substrate core in the anthropological composition of the Altai-Sayan population.

It was possibly an anthropological base not only among the early nomads of Tien Shan and Dzungaria but also of some prior population groups, otherwise has to be assumed their migration from the eastern area of the Southern Eurasian Anthropological Formation.

The Southern Eurasian Anthropological Formation was the anthropological substrate of all known to date autochthonous cultures in the Altai-Sayan region. It became a part of some Afanasev Culture populations.

Its introduction allowed to differentiate clearly the migrant components. Against its background, it became apparent that the impact of migration on the formation of the anthropological composition of the Altai-Sayan populations was somewhat exaggerated.

Archaeological materials show a great geographical scale of the population’s cross-cultural contacts, while the anthropological materials provide a base for a fairly conservative model of the race-forming, anchored on intra-population transformations of its anthropological structure and greater magnitude of local territorial interactions of the population groups.

The results of craniometric and odontological studies are in agreement with the results of the mitochondrial analysis of the genetic samples from the Gorny Altai ancient population, confirming the importance of the local intra-regional interactions between the populations.

That allowed to view the Altai Mountains as a kind of “refugium”, where for several epochs endured a layer of ancient and protomorphic anthropological community. The role of the “refugium” can be extended only to the inner mountainous region of the Altai-Sayan upland. Its open to the north forest-steppe foothills and steppe valleys experienced the great influence of inter-regional scale.

The results of the study demonstrated the Neolithic Era intensity of cross-cultural relations in the Altai and Sayan foothills. Convincing anthropological evidence indicates the direct influence of the Neolithic Serov tribal Culture in the Baikal area on the groups of Altai and Sayan people.

The south-western connections of the Neolithic population in the southern Western Siberia, mainly detected for Bolshemys and Kelteminar Cultures from archaeological sources was not corroborated by anthropological study as a migration impulse and can be explained by existence in a distant past of common genetic (anthropological) substrate of the population, which probably preserved intercultural contacts of the offsprings.

In the Early Metal Period (ca. 2000 BC – 300 AD), in the southern region of the Western Siberia were actively forming cultures whose genesis involved many problems. Within the boundaries of their areas endured two core anthropological communities, which formed the fabric for the morphological traits of the Early Metal Period population.

Studies found anthropological continuity between the people of the Neolithic and Ust-Tartas cultures in the Baraba steppe. Some migrant Afanasev Culture groups in the Altai territory display morphological features pointing to marital interaction with the indigenous population.

Evidence indicates an impulse of Bolshemys Culture from the Barnaul-Biysk-Ob area or their descendants into the anthropological milieu of Ust-Tartas Culture of the Baraba province.

The obvious migratory impulses of animal husbandry population from the Middle East or Middle Asia from the south to the territory of the Altai Mountains are traced by anthropological markers starting from the 2nd mill. BC, and increase in the Early Nomads Era (2nd mill. BC – 1st c. BC).

The population of the Baraba steppe in the Early Bronze Age (32 c. – 23 c. BC ) retained capacity of the indigenous anthropological substrate, having assimilated the impulse of the migrant Bolshemys Culture. The anthropological complex of the Odinov Culture, which replaced the Ust-Tartas Culture, displays features specific to the Neolithic people of the area.

At the classical stage of the Krotov Culture, which replaced Odinov Culture, the anthropological composition of the population contained only autochthonous morphological complex.

Noticeable changes in the anthropological composition of the Baraba province’s population occurred at the final stage of Krotov Culture, which was a period of its coexistence with Andronov (Fedorov) Culture people.

The new morphological features are not associated with the population of Fedorov Culture and strikingly contrast with the distinctive features of Elunin Culture.

Apparently, the migration wave of the Andronov cultural-historical community tribes pushed the inhabitants of the Altai-Sayan foothills to the north into the pre-taiga and southern taiga zones, where conflating their physical type (which ascended to the Southern Eurasian Anthropological Formation) with local tribes (which anthropologically ascended to the Northern Eurasian Anthropological Formation) went on a process of Andronoid Cultures’ ethnogenesis. The same component (Andronov ?) became an ingredient in the late-stage Krotov Culture population.

Judging by the complexity of the Fedorov culture people anthropological composition in the southern Siberia, the migration impulse by the Andronov cultural-historical community tribes impacted many cultures.

In the most active form the ethnic-racial interaction between migrants and indigenous population groups went on in the Baraba steppe and Upper Ob right bank. In the steppes of Altai and Minusinsk Basin, Fedorov Culture retained proto-Caucasoid anthropological type (in its Andronov version), which was probably typical for the founders of the Fedorov cultural traditions.

The anthropological base of the Irmen Culture population was composed of morphological variations within the Southern Eurasian Anthropological Formation. The population of all local-regional variations of the Irmen culture was formed by the West Siberian Andronov group.

The influence of the anthropologic component of the Karasuk Culture is noted at the population of the Tomsk variation of the Irmen Culture, it can be also traced in the female subgroup of the Baraba and Insk versions.

In the cranial series from the burials that were suspected in connection with Begazy-Dandybaev Culture, the male subgroup showed a morphological similarity with people of Andronoid cultural traditions, the female subgroup showed a morphological similarity with Andronov cultural-historical community of northern Kazakhstan.

Such structure of anthropological composition may be indicative of autochthonous Western Siberian substrate of this population and of the structure of its marital relationship, suggesting an influx of women from the Begazy -Dandybaev Culture, who in anthropological terms apparently were similar to the Andronov population of northern Kazakhstan.

In the mountainous regions of the Altai and Sayan Mountains (central Tuva), the anthropological substrate of Early Nomads was comprised of the autochthonous protomorphic anthropological community, ascending to the Southern Eurasian Anthropological Formation.

Changes in the anthropological composition of the population mainly occurred in the second half of the 6th c. BC. In the anthropological composition of the Pazyryk Culture in the Altai Mountains was found a Caucasoid component, genetically ascending to the cattle-breeding population of the northern regions of Asia Minor and southern regions of Central Asia.

At the final stage of the Aldy-Bel Culture of Tuva was noted a component associated with the milieu of Early Sarmatian population, and at the end of the 3rd c. BC in that area is noted impetus from the Northern China population.

The large-scale transcontinental migrations at the beginning of the Metal Epoch (after 40th c. BC including Copper Age, after 31th c. BC beginning with Bronze Age) (Afanasev migration) (3700/3300/2500–2000 BC) and in the Middle Bronze Age (26/25 — 20/19 cc. BC) (Andronov migration) (2100–1400 BC) had no significant modifying effect on the anthropological composition of the indigenous population in the southern region of the Western Siberia.

For the pre-taiga areas of the West Siberian Plain, and for the mountain areas of the Altai-Sayan highlands, in the formation of anthropological composition more important are the internal local interpopulation interactions.

That is evidenced by the stability of the typological trait combinations of two of anthropological communities – the Northern and Southern Anthropological Formations, which zones are not isolated either in spatial geographical, nor historical and cultural relations.